Value based care – reality, promise or a myth? (Part 1)

Is it just me or no matter where you turn your head it seems like Value based care (VBC) is expected to be this magic wand that will reduce healthcare (unnecessary) costs / improve quality / allow company X to be the next super-unicorn?

As this concept is addressed by such a myriad of interpretations, it seems like worth popping the hood and offer some reality check.

As with previous posts, I’ll first try to describe the current situation (spoiler - far less utilization of VBC than you might expect), reflect on the two-sided coin of challenges and opportunities and end with an attempt to learn from the Israeli capitated health system.

What is VBC and Current situation

VBC is a concept that has been around for quite some time. Trying to pin the “kick-off” moment for the US, it seems that the ACA act (2010) might be a suitable candidate. Although the reform was much broader (Medicaid expansion, ACA plans exchange marketplace, etc.), since it’s legislation there was a growing notion of a transition from fee-from-service to value-based care.

Per CMS, value-based care has “three-part aim”:

Better care for individuals

Better health for populations

Lower cost

In essence – better care (quality), for less money.

Sounds rather simple but it is the very opposite. This is a crucial point that I’ll come back to during this post.

A decade ago, CMMI (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation) was established within CMS to oversee demonstration projects and VBC arrangements. In other words, it “supports the development and testing of innovative health care payment and service delivery models.”

The CMMI was given ~$20 Billion in funding and per a recent article published in NEJM by its former director Brad Smith it launched 54 models (i.e. programs) and made VBC actually really prevalent –

“Value-based care has spread rapidly across the country, with approximately 40% of Medicare fee-for-service payments, 30% of commercial payments, and 25% of Medicaid payments today being made through some form of value-based arrangement”

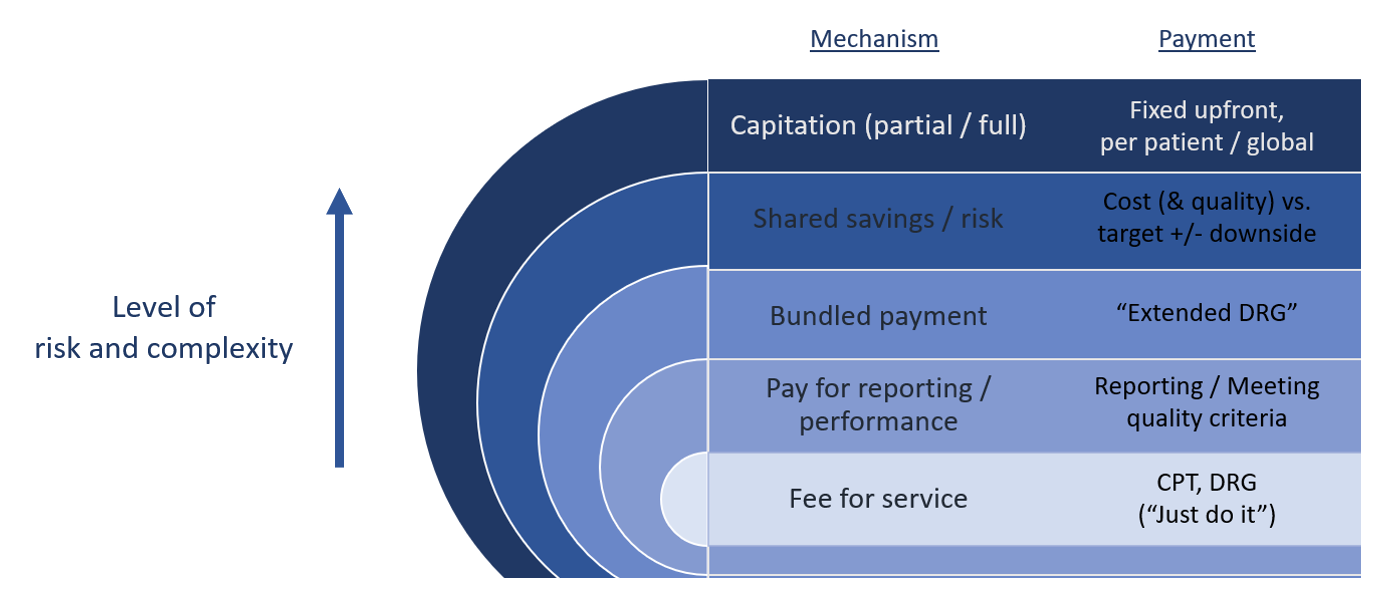

These models revolve around different payment mechanisms (i.e. – APMs; alternative payment models), with a spectrum of risk and required sophistication from the participating provider.

*Downside = paying for losses (negative difference between target and actual price).

The story doesn’t end here. There are “matching” provider organizations (ACO, MCO, HMO, IDN,… ) that facilitate these mechanisms. Essentially, they differ by:

Type / amount of physicians or hospitals that are members in the organization

Degree of patient gate keeping (access to special care via PCP referral or not) and level of care coordination

Possibility for out-of-network care

Physicians treating based on the organization guidelines / standard

Risk sharing elements

Now, although It may seem like there is already a robust infrastructure that allow value-based care, the reality is a bit different. Instead of trying to deep dive on the specific models, programs and different types of provider organization let’s try to examine the entire approach to understand if indeed, there is a shift in the formidable goal of improving quality and reducing costs.

As a teaser, just consider the latest reflection on VBC by the new CMMI director Liz Fowler at the National Association of ACO’s virtual conference (April 21’).

“I’ll be honest, I think we’re at a crossroads right now. Collectively, all of us need to draw on what we’ve learned from the last 10 years and chart a path for the future together…”

“…landscape of value-based care models has gotten more complex with some overlapping and providers having to compete over benchmarks and savings…”

Most of what we currently consider as VBC is actually…. FFS (with some twitches)

In the CMMI NEJM paper that was previously mentioned there is an alarming conclusion -

“…the vast majority of the Center’s models(that is 54 models supported by a $20 billion budget) have not saved money, with several on pace to lose billions of dollars. Similarly, the majority of models do not show significant improvements in quality, although no models show a significant decrease in quality…”

In other words, despite that VBC is quite prevalent as mentioned above, the reality is, well, much less favorable. Major part of the explanation lies within the fact that the vast majority of current APMs actually rely on FFS “foundations”.

According to a report (national scorecard payment reform) released in December 2019 by the Catalyst for Payment Reform, 90% (!) of VBC payment as of 2017 were based on Fee-for-service.

2017? Well things most have improved right? Well, not so much.

Per the “2019 methodology and results report” published by HCPLAN on the progress of alternative payment models, most of APMs are, again, FFS “augmented” by some VBC elements.

This survey, done in mid-2019, is quite extensive – “covered 62 health plans, 7 FFS Medicaid states, and Traditional Medicare, representing approximately 226.5 million of the nation’s covered lives and 77% of the national market.”

Even if I try to be as optimistic as possible and include category 3B as real value based care (FFS with shared saving + downside risk), VBC models (categories 3B and 4) represented less than 15% of all payment models (aggregated data for all type of plans - Commercial, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, and Traditional Medicare)!

There is a great piece recently wrote by Yoav Fisher (head of technological innovation at Health.il) that elaborates nicely on this point.

The elephant in the room - What is actually “value” and how to measure it

To understand the reason for this situation, let’s first start with some fundamentals. The US healthcare system is articulated around fee-for-service. Business models had evolved throughout the years to meet this criterion and maximize profit (the very definition of capitalism). Hospitals were geared to treating a high volume of patients and reduce the number of empty beds / rooms / ORs. Staffing and real state were aimed at maximizing capacity. In other words, the 1st ,2nd ,3rd (…) KPI providers have are linked to volume.

Specific goals deduce specific criteria and tracking methodologies to make sure you (will) meet them. Moving from volume to value is like a 180 degree turn in that perspective. In many cases instead of maximizing treatment, you need to reduce it.

A crucial part here IMO that is less discussed is the need to measure things that these behemoth organization seldom did before (and by all means not at scale).

I once heard from >1000 beds hospital CEO that his facility is like a car factory that mastered the production of a specific model of sedans. They are doing it almost automatically. But if you request just one SUV instead of a sedan – they will fail. Moving from volume to value is like asking them to move from cars to airplanes.

No wonder that instead of making a binary shift, provider takes the middle ground, i.e. “let’s do what we are used to do and good at (FFS) and gradually alter (add some VBC elements)”. You saw the consequences yourself.

It is also important to keep in mind that quality in healthcare might be one of the most diverse concepts out there and can facilitate entire courses. There are so many questions revolving the right approach –

What to measure (outcome, process, NPS, timing / duration, accessibility…)

How to measure (relative vs. absolute, what is the right benchmark, how to quantify qualitative things, weighted averages per different diseases or patients…)

Who you measure (target population, specific physicians / department / hospital)

Who knows he is being measured and what do you tell him (blinded / no-blinded, how much details are you giving him, what are his / hers incentives to collaborate, how to avoid Hawthorne effect)

Again, let’s try to overcome the complexity of this notion by trying to examine it from a 30,000 feet perspective. The problem of “what you measure is what you get” / Goodhart’s law is painfully true in medicine. It might even have an extension in the form of “what you don’t measure will get lost” (or “the multi-tasking” problem) as almost any quality measure means extra work for the department staff (measuring rates of central line infections) and thus less time for other things (monitoring peripheral I.V. lines).

The core assumption is that better quality will lower costs (triple aim…), is… not such a consensus.

Multiple studies tried to assess the impact of quality measurement programs. The conclusion? In most cases using quality measurement didn’t reduce costs or improved outcomes. Part of the explanation is that most quality indices measure specific “items” within a procedure (how much time between E.D. admission and surgery) or specific by products of procedures (readmission after hip replacement, infection rate after CABG) and not the necessity of the procedure itself (does the patient actually need a new hip).

(This point is described in breadth in “The price we pay” by Dr. Marty Makary.)

Measuring cost has its own problems.

Care journeys are complex and prolonged. Costs often incur in different silos (in / out hospital, etc.) which are owned by different stakeholders due to the fragmentation of healthcare. The very core element of sharing cost related (same as quality related) data between these players and health plans / CMS is still SUPER challenging (data normalization, harmonization, exchange,… and maybe the biggest of all – conflicting interest)

There are many curve balls of patients with post procedure complications that seek treatment in a different location. In most cases no connection will be made between the two “activities” and thus no real value / cost appreciation.

Utilization vs. cost & quality

Because it is extremely complicated to demonstrate cost saving or quality improvement, in most cases VBC models rely on a (not so good) surrogate in the form of reduction in healthcare utilization. Utilization is volume and that’s a “language” the system can handle. Accordingly, service companies also demonstrate their value proposition by lower utilization. Take this PR from Vesta Healthcare as an example:

“…Vesta partners with home care agencies, health plans and providers to create value-based population health programs that emphasize clinical quality, improved health outcomes and personalized engagement.

By working with home care agencies, professional aides and unpaid caregivers such as family and friends, Vesta recognized the ability to reduce avoidable hospitalizations, emergency room visits and other facility-based care. Vesta empower caregivers and care teams to improve health outcomes and keep members healthy and cared for at home.

Vesta Healthcare’s program serves as an early warning system to support preventive intervention and avoid unnecessary hospitalizations and other health events that may reduce people’s ability to age safely in their homes.

The Vesta program has shown that 88% of urgent alerts can be managed and resolved in the home in partnership with caregivers, resulting in an over 30% reduction in emergency room visit and hospital admission rates, the company said…”

The thing is, a reduction in a specific healthcare service too often doesn’t lead to the desirable outcome. Emergency department visit can serve as a good case study.

Like in the prior example, many VBC programs hone in E.D. visit reduction. Although there are many unnecessary E.D. visits, they actually take only a small portion in the overall cost of a care journey – less than 5%.

Also a very nice and comprehensive read related to this topic and primary care models.

And there is also a flip side of necessary E.D. visit that were missed due to these programs. I didn’t find concrete numbers, but I’m convinced that the cost of one “false negative” is tremendous compared to the cost of an unnecessary visit that was avoided (true negative). When a patient that truly needs the E.D. doesn’t arrive, his condition can deteriorate dramatically. The “number needed to treat” here would be very high. We come back to the same point, we measure utilization (what / how) and not if a procedure was necessary or not (why)!

Now consider bundle payments.

Providers are measured only against the complications of a certain procedure (that will lead to higher cost than the predetermined bundle payment) but for each new procedure will still get the (bundled) payment, even if it wasn’t necessary or could be avoided. No surprise that the bundle payment models seem to be the one of the biggest money drainers per CMMI.

As tech, regulation and market needs seems to converge, are we entering a pivotal moment for VBC?

The pandemic created a huge blow for FFS models as care volumes dramatically decreased (especially for the more lucrative ambulatory procedures) and providers’ margins were pressured down and still haven’t returned to pre-COVID levels.

(note that this is a Y-Y comparison and thus March 21’ is an outlier as it is matched with the first month after COVID hit)

Value based payments and especially capitated models possess a tremendous “safe harbor” opportunity in that perspective. On top of it, new regulation revolving data interoperability and payment transparency coupled with the advancement of relevant technologies (data abstraction, exchange, inference…) are all converging into meaningful business opportunities.

In the next part I’ll showcase some of them, while also using some very relevant lessons learned from the Israeli healthcare system that rely on the combination between a capitated model and digital infrastructure for almost 3 decades.

Stay tuned 😊

Want these posts instantly in your mailbox?